Overworked peasant women

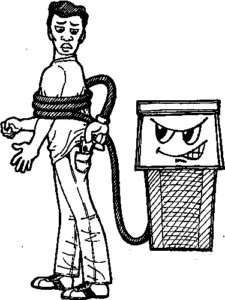

Peasant women are considered an “invisible” part of labor force. Data by the Center for Women’s Resources in 2018 indicated that only 644,000 women were counted by the reactionary state in the agricultural sector. This extremely low figure is attributed to the fact that many peasant women do not own land and are categorized as “housewives.” This is despite their participation in all aspects of production—from planting, applying fertilizers and weeding, to harvesting, drying, repacking and selling. Aside from farming, they also often perform support roles such as cooking, and preparing seeds and other chores.

The hours they allot to house chores and taking care of their children are neither measured nor compensated. As women are traditionally tasked to manage the family’s budget, they are often obliged to borrow money or look for sideline work. Because of this, they are often more indebted than men.

Last year, the participation rate of peasant women in the labor force further shrank despite doubling or tripling their work to make ends meet for their families. They are burdened by the income losses caused by the seemingly endless lockdowns. They could not look for sideline jobs due to movement restrictions even within barrios.

“Our income in 2020 is equivalent to just nearly half of what usually earned in the past,” said Jeni who farms in a small cornfield rented by his husband. They did not have enough pesticides, seeds and fertilizer for production as they failed to procure these prior to the lockdown which ordered the closure of business establishments. Their relatives could not help them in the farm due to lockdown restrictions. They experienced difficulty in selling their produce because there was no means of transportation.

To get by, Jeni worked as a laundry woman twice a week and received ₱250 per day. Despite this, her income is still not enough.

“I’m stressed out whenever I think of how I will strech my small income,” she said. “Instead of rice, my children now often eat corn rice for breakfast. Also, we often do not eat on time.”

Surveys conducted in the Philippines and abroad showed that women experience more stress than men amid the pandemic as they are commonly the ones who take care of their families. As funds dwindle even for daily needs, they become increasingly agitated thinking of how to cover medical expenses should a family member fall sick during the pandemic. The stress is highest among mothers, especially those with children aged 18 and below. This is because they are traditionally tied to responsibilities of caring for and ensuring the health of their children.

In the case of June, three of her children are still in school. Her time is divided into helping her children with their studies and working. “Assisting my children to answer their modules takes up so much time when I could have worked more to earn extra.”

Blended learning also causes tensions between mothers and children. In the case of Thelma, her children could no longer help her in doing house chores as they are also stressed with answering their modules. “I couldn’t even send them on errands,” she said. Although mainly a housewife, Thelma helps her husband in planting and harvesting.

Like Jeni, Norma’s income dropped because of the lockdown. She and her husband earn a living by planting turnips and vegetables. “We weren’t able to sell a portion of our produce,” she said. “Before, we used to sell to schools, that’s why our income dropped.”

To earn extra, Norma is raising pigs and other farm animals. Between looking for places to sell turnips and doing house chores, she has almost no energy to assist her grandchildren who are under her care in their studies.